From the UW Crew Newsletter: An article looking at the Conibear Stroke looking at comparing Rod Johnson to current UW Rowers at http://www.pocockrowingcenter.org/rodjohnson.html

3/14/15

When Rod Johnson died in 2010 Michael Callahan, men's crew coach at the University of Washington, paid a nice tribute to Rod by comparing his stroke in 1950 frame-by-frame with that of his seven man, Max Lang in 2009.

2010

Rod Johnson, Captain 1950, stopped by the Conibear Shellhouse last winter and gave me a Life magazine article from June 20, 1949, that illustrated the "Conibear Stroke" and discussed the influence Washington had on the intercollegiate rowing world. While the article was interesting to me last winter, its connection to the current team became even more compelling when I revisited it this autumn.

The Life article stated: "Nine of the 12 colleges entered at Poughkeepsie this year have coaches who went to Washington, and who now use a modified version of the 'Conibear stroke', which was developed at Washington by the late great Hiram Conibear, the Knute Rockne of collegiate rowing ... The Conibear Stroke consists of a quick even drive with practically no layback. 'It's a lot easier to row sitting up than lying down,' Ulbrickson says."

Rod and I discussed how his coach Al Ulbrickson taught the rowing stroke in his day. While it is a commonly held belief among our alumni that the stroke is much different today than it was 60 years ago, the photos in the Life article provide a visual illustration of how the Conibear stroke is still strikingly similar to the technique we use today.

"When the nation's best eight-oared crews line up on June 25 (1949) for the Intercollegiate Rowing Association's annual regatta at Poughkeepsie, N.Y., the defending champions from the University of Washington will again be the favorites. In five out of the past eight regattas Washington's Huskies have won the varsity championship. Last year, for the third time since 1936, Washington "swept the Hudson" by winning all three Poughkeepsie races varsity, junior varsity and freshman." Sweeping the IRA regatta is an enormous accomplishment that demonstrates top-end speed, overall team depth and race day execution at the very highest level. In the many decades that the IRA regatta has taken place, a sweep has only occurred 15 times. Of those 15 times, the University of Washington is responsible for six of those incredible performances.

Our 2009 IRA performance was a great achievement but we are most proud of the fact that we have continued the tradition of excellence in oarsmanship at Washington.

I found this Life article particularly compelling because of the parallels between Rod's team and ours. 60 years ago we had just swept the IRA, 60 years ago we were rowing the Conibear stroke and 60 years ago our alumni watched eagerly as a new group of Huskies took to the water to defend our title and uphold our tradition of excellence. It was true then and it is true today. Our connection to our history is strong and it is built upon the same tenets as always: hard work, excellence of oarsmanship and the Conibear stroke.

In the next few pages I will compare the 1949 photos of Rod Johnson to the 2009 photos of current senior Max Lang. I will not suggest that one is better than the other. While equipment and technology have had an affect on the stroke, you will discover that the essence of the Conibear or "Washington Stroke" is the same.

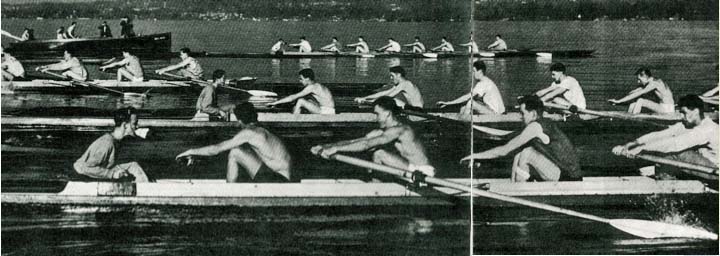

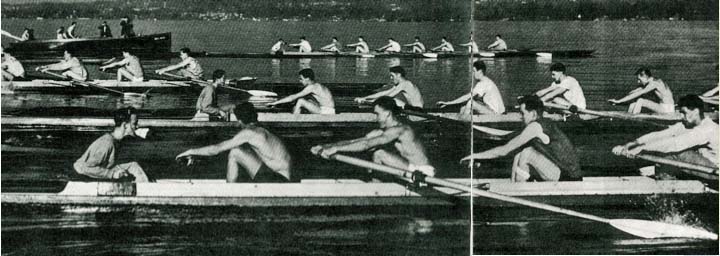

"On Lake Washington, adjoining University campus, shells go through practice session. Stroke of crew in foreground is violating a fundamental rule (eyes in the boat) by looking at the coaches launch (background)" (LIFE)

Rod Johnson '50 (left) and Max Lang '09 (right)

"Conibear stroke begins as Rod Johnson dips oar in the water. It must "catch" in vertical position; slanted, it will go deep and forward motion will be lost" (LIFE). Longer seat tracks in modern boats allow rowers to achieve greater leg compression instead of gaining length from lower back and shoulders.

Compared to today, the 1949 blade shape requires more skill to catch water. Modern oar shapes load somewhat faster.

"Blade is anchored and oar bends slightly as Johnson's back shows strain. Body angle is now set although he will slide back in shell 12 inches as his legs straighten out." (LIFE). Both oarsman are now in the strong position building power in the stroke. (Keep your eyes in the boat, Max!! Some things never change!!)

1949 oar materials were softer, with less blade surface area. Arms bend earlier to keep rower connected ("anchored") to the water. On modern blades, the shaft is stiffer and supports a larger blade surface area. Instead of earlier arm bend, Lang is using more body swing with straight arms to achieve the same connection.

"Body angle is constant, without layback, a whirlpool marking the run of the boat as Johnson lifts blade from water (above) and recovers oar for next stroke (below)" (LIFE).

Johnson uses his shoulders to rebound into the next stroke. Both Johnson and Lang use hand speed out of bow to gain preparation for next stroke. In both cases, their heads lead their hips, helping them to keep connected to the boat through the footstretcher.

Johnson's and Lang's knees soften and start to bend. The recovery is the part of the stroke where the rower wants to let the boat work for him.

The rower prepares to take another stroke. Johnson's blade is closer to the water due to its symmetric shape. Lang's blade is further off the water to make room to square the asymmetrical hatchet blade.

The graph above describes the drive phase of the rowing stroke. This graph recorded the stroke of an elite rower. The Vertical (Y) axis is the force the rower applies to the oar in Newtons. The horizontal (X) axis is the length of stroke on how long (in centimeters) the rower keeps force on the oar. The area under the curve represents the total energy imparted to the oar by the rower. The larger the curve, the more powerful the stroke for the given boat speed. The smooth force curve shows that power is always going "out," meaning that useable power is always being produced. To produce maximum power, the rower needs to be both connected to the boat and the water, AND his stroke must be coordinated.

1. The force curve starts at (1) with the blade anchoring, or connecting, to the water. The "catch" is immediate. 2. Rower loads the oar and builds power in this part of the drive. 3. The rower passes through the maximum peak force of the drive 4 and 5. Past the force peak, the rower maintains his connection with the water. A rower who has good coordination and connection at the beginning of the stroke is better able to maintain his power towards the end of the stroke. 6. Oar releases the water. Rower is now in the recovery phase of the stroke cycle, which is represented on the graph on the next page.

These sample curves illustrate another elite rower's stroke. The green line represents the oar angle at the oar lock through a full stroke cycle. We will follow the angle from release to catch, the recovery phase, since we have already discussed the drive phase of the stroke. 1. The rower's hands leave the finish position towards the stern of the boat. 2. The rower's arms fully extended, shoulders follow hands towards stern. 3. The rower's knees soften and start bending, body angle will soon be set for catch position. 4. The rower's knees rise and thighs approach chest, beginning to square the oar for the catch. 5. The rower's oar is completely square, rower is now matching oar blade speed with boat speed. 6. Rower allows oar to enter water with minimum splash and no check. This is an efficient hatchet oar catch.

These curves show the high level of skill and strength required to make the boat go fast. Equipment and technique must be closely matched for optimum boat speed. Throughout UW's rowing history coaches and student athletes have strived to optimize the complex interaction of equipment, training, and technique and our rowing history tells the story. The Conibear stroke remains a key component of our technique, but some subtle changes have occurred. Differences in the recovery, catch and drive are mainly due to equipment changes and modern materials but the critical, accelerating connection to the water remains the same. Although today's rowing environment brings its own challenges, including the size of the program and cost per athlete, we still continue to apply Washington's core values and the genius of the Conibear Stroke everyday. And with it we strive to bring the very same effort, intensity, and success that were the hallmark of the teams represented by Rod Johnson and his teammates sixty years ago.

|